Perpendicular to a grating falls a parallel bundle of rays. The grating has 5,000 slits per cm. At a distance of 2.00 m is a screen parallel at the grating. The distance between the both 2 e order maxima is 3.20 m. Calculate the wavelength of the light. D = 1/5000 = 2.00 x 10-4 cm = 2.00 x 10-6 m. X 2 = 1.60 m tan α 2 =1.60/2.00 = 0.800.

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have succeeded for the first time in looking inside materials using the method of transient grating spectroscopy with ultrafast X-rays at SwissFEL. The experiment at PSI is a milestone in observing processes in the world of atoms. The researchers are publishing their research results today in the journal Nature Photonics.

The structures on microchips are becoming ever tinier; hard disks write entire encyclopedias on magnetic disks the size of a fingernail. Many technologies are currently breaking through the boundaries of classical physics. But in the nanoworld, other laws apply - those of quantum physics. And there are still many unanswered questions: How does heat actually travel through a semiconductor material at the nanoscale? What exactly happens when individual bits are magnetised in a computer hard disk, and how fast can we write? There are still no answers to these and many more questions mainly because current experimental techniques cannot look deeply and precisely enough into the materials and because some processes take place far too quickly for conventional experimental methods. But if we want to push ahead with technical miniaturisation, we need to understand such phenomena at the atomic level

The mix of methods makes the difference

- THE DIFFRACTION GRATING SPECTROMETER Purpose a. To study diffraction of light using a diffraction grating spectrometer b. To measure the wavelengths of certain lines in the spectrum of the mercury arc lamp. Theory Diffraction grating is a thin film of clear glass or plastic that has a large number of lines per (mm) drawn on it.

- A fixed frame of bars or the like covering an opening to exclude persons, animals, coarse material, or objects while admitting light, air, or fine material. Diffraction grating.

Fresh impetus is now being brought to the matter thanks to a new method devised by PSI researcher Cristian Svetina, together with Jeremy Rouxel and Majed Chergui at EPFL in Lausanne, Keith Nelson at MIT in the USA, Claudio Masciovecchio at Fermi FEL in Italy, and other international partners. 'The method is actually not new, though, and it has been used for decades in the optical regime with exceptional results,' says Svetina, who is currently setting up the new Furka experiment station on the SwissFEL beamline Athos at PSI. What is special, he says, is the combination and extension of known methods from nonlinear laser physics, but using X-ray light from the new X-ray free-electron laser SwissFEL. This combination is both new and surprising. Several attempts have been made in the past by many groups around the world but without success. It has even been questioned whether such novel experiments could be successfully conducted at all at the high energies of X-rays. The team at PSI has proven: Yes, it can be done.

At its core, this is a method called transient grating spectroscopy. Spectroscopy is a proven set of methods used by physicists to obtain information about a material, such as the chemical elements and compounds it consists of, its magnetic properties, and how atoms move within it. In the particular variant called transient grating spectroscopy, the sample is bombarded with two laser beams that create an interference pattern. A third laser beam is diffracted at this pattern, creating a fourth beam that contains the information about the sample's properties.

Looking beneath the surface

The term laser is always used to describe light in the visible or infrared range of the wavelength spectrum. Therefore lasers can look inside a sample only with resolution limited to hundreds of nanometres. To go beyond this, X-rays are needed. Researchers at PSI have now succeeded for the first time in making transient grating spectroscopy accessible to an X-ray laser, using very hard X-rays with an energy of 7.1 kiloelectronvolts, which corresponds to a wavelength of 0.17 nanometres, or about the diameter of medium-sized atoms. The advantage: For the first time, it is possible to look inside materials with a resolution down to individual atoms as well as with ultrashort exposure times of fractions of femtoseconds (one millionth of a billionth of a second), which even allows videos of atomic processes to be recorded. In addition, the method is element-selective, meaning that one can selectively measure specific chemical elements in a mixture of substances. The method complements well established techniques such as inelastic neutron and X-ray scattering, adding better resolution in terms of both time and energy.

In practice, the experimental setup looks like this: SwissFEL sends a beam with a diameter of 0.2 millimetres, consisting of ultrashort X-ray pulses, onto a transmission phase grating made of diamond, which looks like a fine comb under the microscope. Diamond is used because it is not destroyed even by high-energy X-rays. It was made especially for this experiment by Christian David of the Laboratory for Micro and Nanotechnology at PSI. The spacing between the teeth of the comb is two micrometres, but this can go down to nanometres if needed. They break the X-ray beam into fine partial beams that overlap behind the grating, thus creating the transient grating diffraction pattern. Behind the grating, one-to-one images of the grating can be observed, repeated at regular intervals - so-called Talbot planes. If you place a sample in one of these planes, some atoms within it become excited, just as if it was sitting at the location of the grating. Only the atoms that 'see' the X-rays in this periodic modulation are excited, while the neighbours that don't experience the irradiation remain in the ground state. This is the chief attraction of the method, since it enables researchers to selectively excite characteristic domains of interest.

Camera with flash

Excitation of the atoms alone, however, does not provide any information. For this, a kind of camera with a flash is needed to briefly expose the sample. In transient grating spectroscopy, this is done by a laser that targets the sample at an angle and shoots images with a minimal time delay to the X-ray beam from SwissFEL. The information comes out of the back of the sample and hits a detector that records the image. Initial experiments have shown one advantage of the method: It does not produce any unwanted background signal. 'If the atoms are excited, you see a signal; if they are not excited, you see nothing,' Svetina explains. This is extremely valuable when measuring samples that emit only weak signals and that cannot be seen with other techniques where a background obscures the signal.

The fact that Cristian Svetina and his team have managed to do what other researchers have not is due to the creativity and patience of the protagonists. 'We proceeded step by step and did not want to try everything at once,' says the physicist. Five years ago the researchers started experimenting at FERMI FEL with optical light and extended it to extreme ultraviolet light before moving on to X-rays at PSI. Here, instead of examining 'real' samples right away, they used gold foils to test whether the energy was sufficient to excite atoms. They succeeded in burning the lattice pattern from a Talbot plane into the foil. Svetina: 'That's when we knew: If we can even print structures, we can excite atoms with lower intensity.' With this the way was clear for the now successful experiment. Using a sample of bismuth germanate, the researchers were able to show that the method fulfilled all their hopes in terms of spatial and temporal resolution, measurement speed, and element selectivity.

Next goal: everything with X-rays

However, the researchers have not yet taken the final step. So far, only the beam that excites the sample is an X-ray beam. The flash of the camera still comes from a laser, so it is visible light. The pinnacle would be reached if that too were an X-ray beam. Svetina: 'We want to take this final step in the course of the year.' And they have additional support: SLAC's LCLS and the PULSE Institute, both at Stanford in California, the RIKEN SPring-8 centre in Japan, and DESY's FLASH in Germany have joined the collaboration team.

The researchers are publishing their results today in the journal Nature Photonics.

###

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2100 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 400 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research).

Contact

Dr Cristian Svetina

Beamline scientist for the Furka experiment station at the SwissFEL beamline Athos

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 43 56, e-mail: cristian.svetina@psi.ch [English]

Original publication

Hard X-ray Transient Grating Spectroscopy on Bismuth Germanate

Jeremy R. Rouxel, Danny Fainozzi, Roman Mankowsky, Benedikt Rosner, Gediminas Seniutinas,

Riccardo Mincigrucci, Sara Catalini, Laura Foglia, Riccardo Cucini, Florian Doring, Adam Kubec, Frieder Koch, Filippo Bencivenga, Andre Al Haddad, Alessandro Gessini, Alexei A. Maznev, Claudio Cirelli, Simon Gerber, Bill Pedrini, Giulia F. Mancini, Elia Razzoli, Max Burian, Hiroki Ueda, Georgios Pamfilidis,Eugenio Ferrari, Yunpei Deng, Aldo Mozzanica, Philip Johnson, Dmitry Ozerov, Maria Grazia Izzo,Cettina Bottari, Christopher Arrell, Edwin James Divall, Serhane Zerdane, Mathias Sander, Gregor Knopp,Paul Beaud, Henrik Till Lemke, Chris J. Milne, Christian David, Renato Torre, Majed Chergui, Keith A.Nelson, Claudio Masciovecchio, Urs Staub, Luc Patthey and Cristian Svetina

Nature Photonics, 22.04.2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41566-021-00797-9

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the pattern obtained from diffraction grating.

- Explain diffraction grating effects.

Figure 1. The colors reflected by this compact disc vary with angle and are not caused by pigments. Colors such as these are direct evidence of the wave character of light. (credit: Infopro, Wikimedia Commons)

An interesting thing happens if you pass light through a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits, called a diffraction grating. An interference pattern is created that is very similar to the one formed by a double slit (see Figure 2). A diffraction grating can be manufactured by scratching glass with a sharp tool in a number of precisely positioned parallel lines, with the untouched regions acting like slits. These can be photographically mass produced rather cheaply. Diffraction gratings work both for transmission of light, as in Figure 2, and for reflection of light, as on butterfly wings and the Australian opal in Figure 3 or the CD in Figure 1. In addition to their use as novelty items, diffraction gratings are commonly used for spectroscopic dispersion and analysis of light. What makes them particularly useful is the fact that they form a sharper pattern than double slits do. That is, their bright regions are narrower and brighter, while their dark regions are darker. Figure 4 shows idealized graphs demonstrating the sharper pattern. Natural diffraction gratings occur in the feathers of certain birds. Tiny, finger-like structures in regular patterns act as reflection gratings, producing constructive interference that gives the feathers colors not solely due to their pigmentation. This is called iridescence.

Figure 1. A diffraction grating is a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits. (a) Light passing through is diffracted in a pattern similar to a double slit, with bright regions at various angles. (b) The pattern obtained for white light incident on a grating. The central maximum is white, and the higher-order maxima disperse white light into a rainbow of colors.

Figure 2. (a) This Australian opal and (b) the butterfly wings have rows of reflectors that act like reflection gratings, reflecting different colors at different angles. (credits: (a) Opals-On-Black.com, via Flickr (b) whologwhy, Flickr)

Figure 4. Idealized graphs of the intensity of light passing through a double slit (a) and a diffraction grating (b) for monochromatic light. Maxima can be produced at the same angles, but those for the diffraction grating are narrower and hence sharper. The maxima become narrower and the regions between darker as the number of slits is increased.

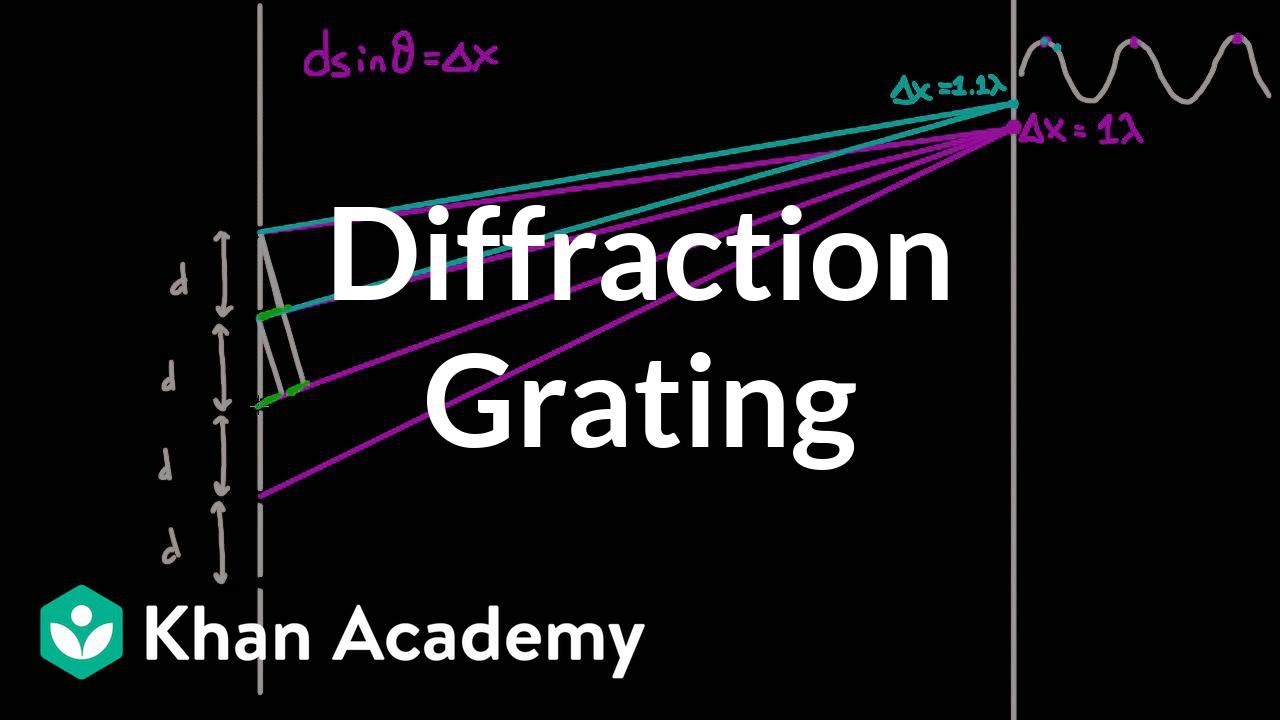

The analysis of a diffraction grating is very similar to that for a double slit (see Figure 5). As we know from our discussion of double slits in Young's Double Slit Experiment, light is diffracted by each slit and spreads out after passing through. Rays traveling in the same direction (at an angle θ relative to the incident direction) are shown in Figure 5. Each of these rays travels a different distance to a common point on a screen far away. The rays start in phase, and they can be in or out of phase when they reach a screen, depending on the difference in the path lengths traveled.

As seen in Figure 5, each ray travels a distance d sin θ different from that of its neighbor, where d is the distance between slits. If this distance equals an integral number of wavelengths, the rays all arrive in phase, and constructive interference (a maximum) is obtained. Thus, the condition necessary to obtain constructive interference for a diffraction grating is d sin θ = mλ, for m = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . (constructive) where d is the distance between slits in the grating, λ is the wavelength of light, and m is the order of the maximum. Note that this is exactly the same equation as for double slits separated by d. However, the slits are usually closer in diffraction gratings than in double slits, producing fewer maxima at larger angles.

In Figure 5, we see a diffraction grating showing light rays from each slit traveling in the same direction. Each ray travels a different distance to reach a common point on a screen (not shown). Each ray travels a distance d sin θ different from that of its neighbor.

Where are diffraction gratings used? Diffraction gratings are key components of monochromators used, for example, in optical imaging of particular wavelengths from biological or medical samples. A diffraction grating can be chosen to specifically analyze a wavelength emitted by molecules in diseased cells in a biopsy sample or to help excite strategic molecules in the sample with a selected frequency of light. Another vital use is in optical fiber technologies where fibers are designed to provide optimum performance at specific wavelengths. A range of diffraction gratings are available for selecting specific wavelengths for such use.

Take-Home Experiment: Rainbows on a CD

The spacing d of the grooves in a CD or DVD can be well determined by using a laser and the equation d sin θ = mλ, form = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . . However, we can still make a good estimate of this spacing by using white light and the rainbow of colors that comes from the interference. Reflect sunlight from a CD onto a wall and use your best judgment of the location of a strongly diffracted color to find the separation d.

Example 1. Calculating Typical Diffraction Grating Effects

Diffraction gratings with 10,000 lines per centimeter are readily available. Suppose you have one, and you send a beam of white light through it to a screen 2.00 m away.

- Find the angles for the first-order diffraction of the shortest and longest wavelengths of visible light (380 and 760 nm).

- What is the distance between the ends of the rainbow of visible light produced on the screen for first-order interference? (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6. The diffraction grating considered in this example produces a rainbow of colors on a screen a distance from the grating. The distances along the screen are measured perpendicular to the x-direction. In other words, the rainbow pattern extends out of the page.

Strategy

The angles can be found using the equation d sin θ = mλ (form = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . ) once a value for the slit spacing d has been determined. Since there are 10,000 lines per centimeter, each line is separated by 1/10,000 of a centimeter. Once the angles are found, the distances along the screen can be found using simple trigonometry.

Solution for Part 1

The distance between slits is [latex]d=frac{1text{ cm}}{10,000}=1.00times10^{-4}text{ cm}[/latex] or 1.00 × 10−6 m. Let us call the two angles θV for violet (380 nm) and θR for red (760 nm). Solving the equation d sin θV = mλ for sin θV, [latex]sintheta_{text{V}}=frac{mlambda_{text{V}}}{d}[/latex], where m = 1 for first order and λV = 380 nm = 3.80 × 10−7 m. Substituting these values gives

[latex]displaystylesintheta_{text{V}}=frac{3.80times10^{-7}text{ m}}{1.00times10^{-6}text{ m}}=0.380[/latex]

Thus the angle θV is θV = sin−1 0.380 = 22.33º.

Similarly,

[latex]displaystylesintheta_{text{R}}=frac{7.60times10^{-7}text{ m}}{1.00times10^{-6}text{ m}}[/latex]

Thus the angle θR is θR = sin−1 0.760 = 49.46º.

Notice that in both equations, we reported the results of these intermediate calculations to four significant figures to use with the calculation in Part 2.

Solution for Part 2

The distances on the screen are labeled yV and yR in Figure 6. Noting that [latex]tantheta=frac{y}{x}[/latex], we can solve for yV and yR. That is, yV = x tan θV = (2.00 m)(tan 22.33º) = 0.815 m and yR = x tan θR = (2.00 m)(tan 49.46º) = 2.338 m.

Contact

Dr Cristian Svetina

Beamline scientist for the Furka experiment station at the SwissFEL beamline Athos

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 43 56, e-mail: cristian.svetina@psi.ch [English]

Original publication

Hard X-ray Transient Grating Spectroscopy on Bismuth Germanate

Jeremy R. Rouxel, Danny Fainozzi, Roman Mankowsky, Benedikt Rosner, Gediminas Seniutinas,

Riccardo Mincigrucci, Sara Catalini, Laura Foglia, Riccardo Cucini, Florian Doring, Adam Kubec, Frieder Koch, Filippo Bencivenga, Andre Al Haddad, Alessandro Gessini, Alexei A. Maznev, Claudio Cirelli, Simon Gerber, Bill Pedrini, Giulia F. Mancini, Elia Razzoli, Max Burian, Hiroki Ueda, Georgios Pamfilidis,Eugenio Ferrari, Yunpei Deng, Aldo Mozzanica, Philip Johnson, Dmitry Ozerov, Maria Grazia Izzo,Cettina Bottari, Christopher Arrell, Edwin James Divall, Serhane Zerdane, Mathias Sander, Gregor Knopp,Paul Beaud, Henrik Till Lemke, Chris J. Milne, Christian David, Renato Torre, Majed Chergui, Keith A.Nelson, Claudio Masciovecchio, Urs Staub, Luc Patthey and Cristian Svetina

Nature Photonics, 22.04.2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41566-021-00797-9

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the pattern obtained from diffraction grating.

- Explain diffraction grating effects.

Figure 1. The colors reflected by this compact disc vary with angle and are not caused by pigments. Colors such as these are direct evidence of the wave character of light. (credit: Infopro, Wikimedia Commons)

An interesting thing happens if you pass light through a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits, called a diffraction grating. An interference pattern is created that is very similar to the one formed by a double slit (see Figure 2). A diffraction grating can be manufactured by scratching glass with a sharp tool in a number of precisely positioned parallel lines, with the untouched regions acting like slits. These can be photographically mass produced rather cheaply. Diffraction gratings work both for transmission of light, as in Figure 2, and for reflection of light, as on butterfly wings and the Australian opal in Figure 3 or the CD in Figure 1. In addition to their use as novelty items, diffraction gratings are commonly used for spectroscopic dispersion and analysis of light. What makes them particularly useful is the fact that they form a sharper pattern than double slits do. That is, their bright regions are narrower and brighter, while their dark regions are darker. Figure 4 shows idealized graphs demonstrating the sharper pattern. Natural diffraction gratings occur in the feathers of certain birds. Tiny, finger-like structures in regular patterns act as reflection gratings, producing constructive interference that gives the feathers colors not solely due to their pigmentation. This is called iridescence.

Figure 1. A diffraction grating is a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits. (a) Light passing through is diffracted in a pattern similar to a double slit, with bright regions at various angles. (b) The pattern obtained for white light incident on a grating. The central maximum is white, and the higher-order maxima disperse white light into a rainbow of colors.

Figure 2. (a) This Australian opal and (b) the butterfly wings have rows of reflectors that act like reflection gratings, reflecting different colors at different angles. (credits: (a) Opals-On-Black.com, via Flickr (b) whologwhy, Flickr)

Figure 4. Idealized graphs of the intensity of light passing through a double slit (a) and a diffraction grating (b) for monochromatic light. Maxima can be produced at the same angles, but those for the diffraction grating are narrower and hence sharper. The maxima become narrower and the regions between darker as the number of slits is increased.

The analysis of a diffraction grating is very similar to that for a double slit (see Figure 5). As we know from our discussion of double slits in Young's Double Slit Experiment, light is diffracted by each slit and spreads out after passing through. Rays traveling in the same direction (at an angle θ relative to the incident direction) are shown in Figure 5. Each of these rays travels a different distance to a common point on a screen far away. The rays start in phase, and they can be in or out of phase when they reach a screen, depending on the difference in the path lengths traveled.

As seen in Figure 5, each ray travels a distance d sin θ different from that of its neighbor, where d is the distance between slits. If this distance equals an integral number of wavelengths, the rays all arrive in phase, and constructive interference (a maximum) is obtained. Thus, the condition necessary to obtain constructive interference for a diffraction grating is d sin θ = mλ, for m = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . (constructive) where d is the distance between slits in the grating, λ is the wavelength of light, and m is the order of the maximum. Note that this is exactly the same equation as for double slits separated by d. However, the slits are usually closer in diffraction gratings than in double slits, producing fewer maxima at larger angles.

In Figure 5, we see a diffraction grating showing light rays from each slit traveling in the same direction. Each ray travels a different distance to reach a common point on a screen (not shown). Each ray travels a distance d sin θ different from that of its neighbor.

Where are diffraction gratings used? Diffraction gratings are key components of monochromators used, for example, in optical imaging of particular wavelengths from biological or medical samples. A diffraction grating can be chosen to specifically analyze a wavelength emitted by molecules in diseased cells in a biopsy sample or to help excite strategic molecules in the sample with a selected frequency of light. Another vital use is in optical fiber technologies where fibers are designed to provide optimum performance at specific wavelengths. A range of diffraction gratings are available for selecting specific wavelengths for such use.

Take-Home Experiment: Rainbows on a CD

The spacing d of the grooves in a CD or DVD can be well determined by using a laser and the equation d sin θ = mλ, form = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . . However, we can still make a good estimate of this spacing by using white light and the rainbow of colors that comes from the interference. Reflect sunlight from a CD onto a wall and use your best judgment of the location of a strongly diffracted color to find the separation d.

Example 1. Calculating Typical Diffraction Grating Effects

Diffraction gratings with 10,000 lines per centimeter are readily available. Suppose you have one, and you send a beam of white light through it to a screen 2.00 m away.

- Find the angles for the first-order diffraction of the shortest and longest wavelengths of visible light (380 and 760 nm).

- What is the distance between the ends of the rainbow of visible light produced on the screen for first-order interference? (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6. The diffraction grating considered in this example produces a rainbow of colors on a screen a distance from the grating. The distances along the screen are measured perpendicular to the x-direction. In other words, the rainbow pattern extends out of the page.

Strategy

The angles can be found using the equation d sin θ = mλ (form = 0, 1, −1, 2, −2, . . . ) once a value for the slit spacing d has been determined. Since there are 10,000 lines per centimeter, each line is separated by 1/10,000 of a centimeter. Once the angles are found, the distances along the screen can be found using simple trigonometry.

Solution for Part 1

The distance between slits is [latex]d=frac{1text{ cm}}{10,000}=1.00times10^{-4}text{ cm}[/latex] or 1.00 × 10−6 m. Let us call the two angles θV for violet (380 nm) and θR for red (760 nm). Solving the equation d sin θV = mλ for sin θV, [latex]sintheta_{text{V}}=frac{mlambda_{text{V}}}{d}[/latex], where m = 1 for first order and λV = 380 nm = 3.80 × 10−7 m. Substituting these values gives

[latex]displaystylesintheta_{text{V}}=frac{3.80times10^{-7}text{ m}}{1.00times10^{-6}text{ m}}=0.380[/latex]

Thus the angle θV is θV = sin−1 0.380 = 22.33º.

Similarly,

[latex]displaystylesintheta_{text{R}}=frac{7.60times10^{-7}text{ m}}{1.00times10^{-6}text{ m}}[/latex]

Thus the angle θR is θR = sin−1 0.760 = 49.46º.

Notice that in both equations, we reported the results of these intermediate calculations to four significant figures to use with the calculation in Part 2.

Solution for Part 2

The distances on the screen are labeled yV and yR in Figure 6. Noting that [latex]tantheta=frac{y}{x}[/latex], we can solve for yV and yR. That is, yV = x tan θV = (2.00 m)(tan 22.33º) = 0.815 m and yR = x tan θR = (2.00 m)(tan 49.46º) = 2.338 m.

The distance between them is therefore yR − yV = 1.52 m.

Discussion

The large distance between the red and violet ends of the rainbow produced from the white light indicates the potential this diffraction grating has as a spectroscopic tool. The more it can spread out the wavelengths (greater dispersion), the more detail can be seen in a spectrum. This depends on the quality of the diffraction grating—it must be very precisely made in addition to having closely spaced lines.

Section Summary

A diffraction grating is a large collection of evenly spaced parallel slits that produces an interference pattern similar to but sharper than that of a double slit.

There is constructive interference for a diffraction grating when d sin θ = mλ (for m = 0 , 1, –1, 2, –2, …), where d is the distance between slits in the grating, λ is the wavelength of light, and m is the order of the maximum.

Conceptual Questions

- What is the advantage of a diffraction grating over a double slit in dispersing light into a spectrum?

- What are the advantages of a diffraction grating over a prism in dispersing light for spectral analysis?

- Can the lines in a diffraction grating be too close together to be useful as a spectroscopic tool for visible light? If so, what type of EM radiation would the grating be suitable for? Explain.

- If a beam of white light passes through a diffraction grating with vertical lines, the light is dispersed into rainbow colors on the right and left. If a glass prism disperses white light to the right into a rainbow, how does the sequence of colors compare with that produced on the right by a diffraction grating?

- Suppose pure-wavelength light falls on a diffraction grating. What happens to the interference pattern if the same light falls on a grating that has more lines per centimeter? What happens to the interference pattern if a longer-wavelength light falls on the same grating? Explain how these two effects are consistent in terms of the relationship of wavelength to the distance between slits.

- Suppose a feather appears green but has no green pigment. Explain in terms of diffraction.

- It is possible that there is no minimum in the interference pattern of a single slit. Explain why. Is the same true of double slits and diffraction gratings?

Problems & Exercises

- A diffraction grating has 2000 lines per centimeter. At what angle will the first-order maximum be for 520-nm-wavelength green light?

- Find the angle for the third-order maximum for 580-nm-wavelength yellow light falling on a diffraction grating having 1500 lines per centimeter.

- How many lines per centimeter are there on a diffraction grating that gives a first-order maximum for 470-nm blue light at an angle of 25.0º?

- What is the distance between lines on a diffraction grating that produces a second-order maximum for 760-nm red light at an angle of 60.0º?

- Calculate the wavelength of light that has its second-order maximum at 45.0º when falling on a diffraction grating that has 5000 lines per centimeter.

- An electric current through hydrogen gas produces several distinct wavelengths of visible light. What are the wavelengths of the hydrogen spectrum, if they form first-order maxima at angles of 24.2º, 25.7º, 29.1º, and 41.0º when projected on a diffraction grating having 10,000 lines per centimeter?

- (a) What do the four angles in the above problem become if a 5000-line-per-centimeter diffraction grating is used? (b) Using this grating, what would the angles be for the second-order maxima? (c) Discuss the relationship between integral reductions in lines per centimeter and the new angles of various order maxima.

- What is the maximum number of lines per centimeter a diffraction grating can have and produce a complete first-order spectrum for visible light?

- The yellow light from a sodium vapor lamp seems to be of pure wavelength, but it produces two first-order maxima at 36.093º and 36.129º when projected on a 10,000 line per centimeter diffraction grating. What are the two wavelengths to an accuracy of 0.1 nm?

- What is the spacing between structures in a feather that acts as a reflection grating, given that they produce a first-order maximum for 525-nm light at a 30.0º angle?

- Structures on a bird feather act like a reflection grating having 8000 lines per centimeter. What is the angle of the first-order maximum for 600-nm light?

- An opal such as that shown in Figure 2 acts like a reflection grating with rows separated by about 8 μm. If the opal is illuminated normally, (a) at what angle will red light be seen and (b) at what angle will blue light be seen?

- At what angle does a diffraction grating produces a second-order maximum for light having a first-order maximum at 20.0º?

- Show that a diffraction grating cannot produce a second-order maximum for a given wavelength of light unless the first-order maximum is at an angle less than 30.0º.

- If a diffraction grating produces a first-order maximum for the shortest wavelength of visible light at 30.0º, at what angle will the first-order maximum be for the longest wavelength of visible light?

- (a) Find the maximum number of lines per centimeter a diffraction grating can have and produce a maximum for the smallest wavelength of visible light. (b) Would such a grating be useful for ultraviolet spectra? (c) For infrared spectra?

- (a) Show that a 30,000-line-per-centimeter grating will not produce a maximum for visible light. (b) What is the longest wavelength for which it does produce a first-order maximum? (c) What is the greatest number of lines per centimeter a diffraction grating can have and produce a complete second-order spectrum for visible light?

- A He–Ne laser beam is reflected from the surface of a CD onto a wall. The brightest spot is the reflected beam at an angle equal to the angle of incidence. However, fringes are also observed. If the wall is 1.50 m from the CD, and the first fringe is 0.600 m from the central maximum, what is the spacing of grooves on the CD?

- The analysis shown in the figure below also applies to diffraction gratings with lines separated by a distance d. What is the distance between fringes produced by a diffraction grating having 125 lines per centimeter for 600-nm light, if the screen is 1.50 m away?

Figure 6. The distance between adjacent fringes is [latex]Delta y=frac{xlambda}{d}[/latex], assuming the slit separation d is large compared with λ.

- Unreasonable Results. Red light of wavelength of 700 nm falls on a double slit separated by 400 nm. (a) At what angle is the first-order maximum in the diffraction pattern? (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

- Unreasonable Results. (a) What visible wavelength has its fourth-order maximum at an angle of 25.0º when projected on a 25,000-line-per-centimeter diffraction grating? (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

- Construct Your Own Problem. Consider a spectrometer based on a diffraction grating. Construct a problem in which you calculate the distance between two wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation in your spectrometer. Among the things to be considered are the wavelengths you wish to be able to distinguish, the number of lines per meter on the diffraction grating, and the distance from the grating to the screen or detector. Discuss the practicality of the device in terms of being able to discern between wavelengths of interest.

Glossary

constructive interference for a diffraction grating: occurs when the condition d sin θ = mλ (form = 0,1,–1,2,–2, . . .) is satisfied, where d is the distance between slits in the grating, λ is the wavelength of light, and m is the order of the maximum

diffraction grating: a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits

Selected Solution to Problems & Exercises

Grating Meaning In Physics Definition

1. 5.97º

3. 8.99 × 103

5. 707 nm

7. (a) 11.8º,12.5º,14.1º,19.2º; (b) 24.2º,25.7º,29.1º,41.0º; (c) Decreasing the number of lines per centimeter by a factor of x means that the angle for the x-order maximum is the same as the original angle for the first-order maximum.

9. 589.1 nm and 589.6 nm

11. 28.7º

13. 43.2º

Define Grating In Physics

15. 90.0º

17. (a) The longest wavelength is 333.3 nm, which is not visible; (b) 333 nm (UV); (c) 6.58 × 103 cm

19. 1.13 × 10−2 m

21. (a) 42.3 nm; (b) Not a visible wavelength. The number of slits in this diffraction grating is too large. Etching in integrated circuits can be done to a resolution of 50 nm, so slit separations of 400 nm are at the limit of what we can do today. This line spacing is too small to produce diffraction of light.